With Russian attacks on Ukraine’s Power Infrastructure Unrelenting, Joe Barnes heads to Kyiv’s Podil district to see how locals are preparing for a third tough winter with limited power.

Olha Marchenko stands panting on the fifth-floor landing, clutching the windowsill for support. A pair of shopping bags lie sprawled at her feet.

“Do you need some help with those?” I ask her.

“It’s fine, leave them,” she snaps, batting my hand away. “I’ve only got another two floors anyway.”

I take my leave reluctantly; the eighty-four-year-old doesn’t strike me as a woman to be trifled with. Her struggle puts my woes into perspective. The power in our building has gone out, taking the internet with it, and foiling my plans to take a video call. But no power also means no elevator, so when an elderly lady like Olha has to do her shopping, she has to climb the seven floors to her apartment unaided.

The Timetable

Ukraine has been struggling with power supplies since Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022, but things have rarely been as bad as they are now. Another wave of strikes across the country in late August signalled Russia’s intention to cripple Ukraine’s energy infrastructure before the winter sets in. According to the Royal United Services Institute, a British think tank, Ukraine is now producing just a third of the electricity as it did before the full-scale invasion.

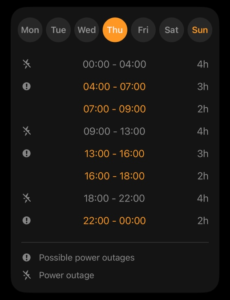

Electricity must now be rationed, leading to rolling blackouts which can last for anything from twelve to eighteen hours a day. In the capital, there is a specific electricity timetable for each of the six districts, divided into those times when you will have power; times when you won’t have power; and times where you might have power, but nobody can guarantee it.

Credit: Joe Barnes

This Thursday, for example, in Podil district, where Olha lives, there are four hours of guaranteed power, eight of possible power, and twelve of blackouts. These blackout periods see the district totally cut off from the grid, and locals must put up without things that we all take for granted. It’s not just the elevator and the internet – Olha’s biggest concern is the loss of power for her fridge-freezer, which means she has to take the stairs to the shops almost every day.

Blackout Life

Locals have done their best to adapt. During a blackout period, the streets rumble with the hum of thousands of generators, most of which run off petrol. Cafés, bars and restaurants in Podil – loosely akin to Kyiv’s Shoreditch or Williamsburg – are almost all equipped with a chugging motor by the roadside. Craft Café on Voloska Street, where I go to take my call, has round-the-clock internet. Their generator also provides them with enough capacity to keep the basic functions of the establishment going.

“We’ve developed a blackout menu,” says the manager, Nastasiya Bilyk. “Ovens are very expensive to power, but we have gas hobs, so we can still prepare most meals – soups, pasta sandwiches… that sort of thing. The coffee machine takes up a lot of power though, so we generally offer just filter coffee during these periods.”

Other caterers have turned adversity into opportunity. Many pizza restaurants were quick to switch their electric ovens to a more authentic wood-fired fare. Meanwhile the Anfield Pub, a sports bar on the left bank of the river, serves food from an outdoor barbecue in the blackout hours.

“You just have to get through it,” Mariia Tsvelikh, a graphic designer from the capital tells me over drinks outside Grails Bar, a popular haunt of twenty-somethings in the tech industry. “There is a proverb here: if you want to live, you have to be able to spin.”

The changing seasons

But one thing that can’t run on gas or wood is the air-conditioning. In the summer months, when temperatures regularly reached thirty-five degrees Celsius, this made life extremely uncomfortable.

“Luckily my apartment building doesn’t get too hot,” says Mariia. “But even so I still bought a small fan with a rechargeable battery. To be honest, I just got out of the country in July, the heat was crazy.”

Still, few people are glad to see the back of the summer heat. The shadow of winter now looms in everyone’s imagination. Soon the problem will turn from a lack of air-conditioning to a lack of light. On December 21st, the shortest day of the year, the sun will rise at 7.56am and set at 3.56pm, giving Kyiv’s residents a grand total of eight hours of daylight.

Even now, in smaller stores, customers search for their items by torchlight during the blackout hours, before having to make payment in cash or by QR code as the card machine has stopped working. By sundown, the streetlights are all off and the traffic lights intermittent. In July, Ukrainian media reported that the loss of traffic lights had led to an increase in accidents across the country. Pedestrians have become accustomed to donning high-viz armbands to warn drivers of their presence.

Solutions

Credit: Joe Barnes.

While individuals do what they can to adapt, the government is scrambling to shore up supplies. The mayor of Kyiv, Vitaly Klitschko, has stated that the city is subsidising the purchase of solar panels for apartment buildings. The central government, meanwhile, has mandated the installation of solar panels on government buildings and scrapped VAT and customs duties on energy-related equipment.

Another answer has been to import more electricity from the European Union. Indeed, Ukraine imported more electricity from the EU in June this year than in the entirety of 2023. Countries have pledged to increase these supplies, Slovakia being the latest to announce its plans to help Ukraine stabilise its grid this winter.

But these are unlikely to have immediate short-term impact. Integration with the EU grid is expected to provide an extra 1.7GW of power. For context, Ukraine usually generated around 25 GW in 2021, these days 9 GW is a success.

Key to the power grid’s survival this winter will be the resilience of the current supply. Over half of Ukraine’s electrical needs are currently met by just nine nuclear reactors. Russia has yet to target these directly, presumably due to the unpredictable consequences of a nuclear explosion. Instead, it has targeted the substations that deliver power to the reactors in an attempt to put them out of action.

Kyiv has spent the summer reinforcing these substations and other critical pieces of infrastructure with both sandbags and reinforced concrete. Officials claim that most are now able to withstand drone attacks. But a direct hit from a larger missile is another matter, and Russia has proved on numerous occasions over the past year that it is capable of overwhelming Ukraine’s air defences with a sophisticated mass attack.

The worst-case scenario would be a successful Russian campaign to degrade Ukraine’s grid over the coming months combined with a very cold winter, with temperatures dropping double digits below zero. The past two winters have been comparably mild, but officials are under no illusions that a prolonged cold snap would stretch the country’s capacity to maintain water and heating supplies.

Olha, however, is trying to look on the bright side. “We all know it’s going to be another hard winter, but we got through the last one. I won’t need to do so much shopping either – in winter, my balcony is my refrigerator.”

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Global Dynamic or its editorial team.